A Parable By Aubrey Menen

O

|

NCE UPON A TIME there was a

discontented tiger. He was not only tired of living in the jungle – although he

thought the jungle was indeed a very silly place, all trees, trees, trees; he

was not only tired of having a striped coat – although he thought that stripes

were a silly design, just a lot of brown lines on a lot of yellow; he was

deep-down discontented with being a tiger.

NCE UPON A TIME there was a

discontented tiger. He was not only tired of living in the jungle – although he

thought the jungle was indeed a very silly place, all trees, trees, trees; he

was not only tired of having a striped coat – although he thought that stripes

were a silly design, just a lot of brown lines on a lot of yellow; he was

deep-down discontented with being a tiger. He put this point of view to three other tigers.

‘Don’t you feel dissatisfied with just being a tiger?’ he asked them.

One of them yawned so as to show off his magnificent teeth. ‘Why should I be? Who has as lovely teeth as I have?’ he said. One of them pretended he saw something move in the grasses, and leaped thirty feet in one bound to find out what it was.

'Dissatisfied?' He called back from among the grasses, ‘just find me an animal who can beat that leap.’

But the last one was a thoughtful tiger and he put a paw on the discontented tiger’s shoulder and said, ‘I know just how you feel!’

The discontented tiger was very grateful and said, ‘Do you really?’

The other tiger said, ‘Yes’ in a sympathetic voice. ‘It’s a sort of empty feeling, isn’t it?’

‘That’s it. That’s just it,’ said the discontented tiger. Fancy you having it too.’

The other tiger gave a shout of laughter (which sounded rather like laughing down a well) and slapped the discontented tiger on the back so hard that he fell over.

‘It’s nothing that a good hearty meal of buffalo won’t cure,’ he said, and all the three tigers started laughing together.

The discontented tiger picked himself up, shook the dust from his coat, and said, ‘This is what I mean. Tigers have coarse minds,’ and he went off into the jungle with his head in the air.

*

*

B

|

UT THE PLEASURE of having been rude

to the other tigers did not last for very long. He went on walking till he came

to a road and then sat down on his haunches to think things out. He curled his tail

round so that the end of it lay comfortably across his front paws, and waited.

Usually, curling his tail round his paws brought the most beautiful thoughts

into his head, but not to-day. He unwound his tail and curled it the other way. But not even that did any good. He just sat there, feeling very low, and

wishing that he itched behind the ears to that he could scratch himself with

his hind leg. That usually passed five minutes off so quite pleasantly, but

to-day he did not even itch.

He looked up and down the road to see if there was anything to take his mind off his troubles, but it was quite empty. A fly started buzzing round his head and he snapped at it. At the very first snap he caught it, so even that failed him as an amusement. Then he saw a dog. It was trotting down the road with the busy, but worried expression which dogs always have when they’re trotting by themselves, as though they are engaged on some urgent business which shows no prospect of being successful. When the dog was about level with him, the tiger said, ‘Well, hullo!’

The dog leapt straight up in the air and fell down on his back.

‘My!’ said the tiger, ‘you did take a tumble. Won’t come up here and rest a bit till you get your breath back?’ Seeing the dog hesitate he added, ‘Please do. I must talk to someone or I shall burst into tears.’

Now, the dog was a very ordinary dog, who had no ambition except to be left alone and allowed to go on quietly with his own affairs. He had found from experience that the best way to make sure of this was to agree with what everybody said to him, and never get into arguments. Naturally, everybody liked him and thought him very intelligent, for a dog, and he was quite used to people telling him their troubles. He made it a principle never to say ‘If I were you.’ He was very popular with people in trouble. So the dog went and sat beside the tiger.

He was rather nervous, of course, and he began the conversation in a somewhat confused manner.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘you gave me a fright and no mistake. I thought you were a tiger.’

‘I am,’ said the tiger : ‘unfortunately.’

‘Ah,’ said the dog, nodding his head, ‘I understand.’ Although he had no idea what the tiger was talking about.

‘I wonder if you do,’ the tiger said, not wishing to be caught a second time that day.

‘Oh yes,’ said the dog, ‘I understand. Not half I don’t. It must be awful.’

‘What must be awful?’ asked the tiger.

‘What you said. Don’t make me talk about it,’ and the dog shook his head again very sadly.

‘But that’s just what I want to do. I want to talk about it,’ said the tiger.

‘That’s right. Nothing like a good talk, I always say. Two heads are better than one, if they’re only sheep’s heads.’

‘You’re very confusing,’ said the tiger; ‘we’re neither of us exactly sheep.’

‘You bet your life we’re not,’ said the dog sagely.

‘No,’ said the tiger; ‘you’re a dog.’

‘Right,’ the dog agreed crisply.

‘And I am a tiger’

‘Right again.’

‘As I remarked when we began this conversation,’ added the tiger, feeling that they had not got very far. But all the same he felt better. ‘I’m so tired of being a tiger,’ he went on. ‘I don’t suppose it’s very exciting being a dog, is it?’

‘It’s terrible, just terrible,’ said the dog.

‘Why?’

‘No prospects. No variety. Nothing to it. What does it add up to after all? Puppy. Dog. Dead dog – and there you are.’

‘I do feel we could do something better with our lives than just being a tiger and a dog. I men, a dog and a tiger,’ he corrected himself politely.

‘You took the worlds right out of my mouth,’ said the dog.

‘Now how would you suggest we go about it?’ asked the tiger.

This had never happened to the dog before. People were usually busy talking about themselves that they never stopped to enquire about his opinions. It worried him a good deal. He did not want to offend the tiger. He had heard that they were quick tempered animals. Then he had an inspiration.

‘We might walk on our hind legs,’ he said.

‘Is that very inspiring?’ asked the tiger doubtfully.

The dog did not like the tone of the tiger’s voice, so he just plunged on: ‘And use our front paws as hands.’

‘Oh yes, quite,’ said the tiger. He had no idea what hands were but he felt that the dog would think he was not intellectual enough if he admitted it, and might stop talking to him.

‘Then we could live in houses,’ and the dog explained what a house was. ‘We could wear clothes,’ and the dog explained that too. He went on talking and talking, describing all he knew about the village up the road and the people in it, until the tiger thought he was the greatest genius he had ever met.

‘But all this is wonderful,’ said the tiger. I don’t know how you can manage to think such things. I’m so very grateful to you.’

‘Don’t mention it,’ said the dog, ‘anything to oblige.’

‘You don’t know what you’ve done for me,’ said the tiger, getting rather sentimental. ‘Before I met you I was so depressed I could have laid down and died. I thought that there was nothing beyond being a tiger. Nothing higher and nobler. But now you’ve given me something to live for. Do you think,' he said anxiously, ‘that an ordinary tiger like myself could ever hope – I mean if he tried very hard – to be a wonderful person like the ones you described so well?’

The dog looked at him critically. ‘I shouldn’t wonder,’ he said.

‘Oh, I’m so glad. I shall go away into the forest by myself for a bit and practise. Hind legs, I think you said. Yes, I have very strong hind legs,’ he said, thinking of his tiger muscles for the first time with a certain amount of satisfaction. ‘Then there are clothes,’ he said. ‘Clothes.’ Suddenly his spirits went down again and he said, ‘Oh dear, oh dear, it’s all so difficult. I’ll never be able to do it.’

The dog felt a splash on the top of his head and he was just about to say ‘Hullo, raining’ as he always said whenever there was a shower. Then he looked up and saw that big tears were running down the tiger’s cheeks and dripping off the end of his whiskers. The dog felt really sorry for the tiger, and for the first time in his life he broke his rule.

‘Oh, things aren’t as bad as all that,’ he said. ‘Some people manage it.’

‘Who?’ said the tiger, sniffing.

‘People,’ the dog replied, ‘in the forest. You’ll meet them one day maybe.’

'Shall I?' said the tiger excitedly, wriggling his whiskers to get rid of all the tears. ‘How wonderful. But I wouldn’t like to meet them until I can do all the things that they can do. Or least some of them. I’d be so ashamed to be an ordinary good-for-nothing tiger.’

‘That’s the spirit,’ said the dog. ‘Never say die.’

‘I shall start practising straight away.’

‘Easy does it,’ said the dog. ‘Well, I must be off. It’s been nice knowing you.’

It’s been nice knowing you.’

‘Much obliged, I’m sure,’ said the dog, and he trotted off down the road, worrying about his business, which still did not look at all hopeful.

He looked up and down the road to see if there was anything to take his mind off his troubles, but it was quite empty. A fly started buzzing round his head and he snapped at it. At the very first snap he caught it, so even that failed him as an amusement. Then he saw a dog. It was trotting down the road with the busy, but worried expression which dogs always have when they’re trotting by themselves, as though they are engaged on some urgent business which shows no prospect of being successful. When the dog was about level with him, the tiger said, ‘Well, hullo!’

The dog leapt straight up in the air and fell down on his back.

‘My!’ said the tiger, ‘you did take a tumble. Won’t come up here and rest a bit till you get your breath back?’ Seeing the dog hesitate he added, ‘Please do. I must talk to someone or I shall burst into tears.’

Now, the dog was a very ordinary dog, who had no ambition except to be left alone and allowed to go on quietly with his own affairs. He had found from experience that the best way to make sure of this was to agree with what everybody said to him, and never get into arguments. Naturally, everybody liked him and thought him very intelligent, for a dog, and he was quite used to people telling him their troubles. He made it a principle never to say ‘If I were you.’ He was very popular with people in trouble. So the dog went and sat beside the tiger.

He was rather nervous, of course, and he began the conversation in a somewhat confused manner.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘you gave me a fright and no mistake. I thought you were a tiger.’

‘I am,’ said the tiger : ‘unfortunately.’

‘Ah,’ said the dog, nodding his head, ‘I understand.’ Although he had no idea what the tiger was talking about.

‘I wonder if you do,’ the tiger said, not wishing to be caught a second time that day.

‘Oh yes,’ said the dog, ‘I understand. Not half I don’t. It must be awful.’

‘What must be awful?’ asked the tiger.

‘What you said. Don’t make me talk about it,’ and the dog shook his head again very sadly.

‘But that’s just what I want to do. I want to talk about it,’ said the tiger.

‘That’s right. Nothing like a good talk, I always say. Two heads are better than one, if they’re only sheep’s heads.’

‘You’re very confusing,’ said the tiger; ‘we’re neither of us exactly sheep.’

‘You bet your life we’re not,’ said the dog sagely.

‘No,’ said the tiger; ‘you’re a dog.’

‘Right,’ the dog agreed crisply.

‘And I am a tiger’

‘Right again.’

‘As I remarked when we began this conversation,’ added the tiger, feeling that they had not got very far. But all the same he felt better. ‘I’m so tired of being a tiger,’ he went on. ‘I don’t suppose it’s very exciting being a dog, is it?’

‘It’s terrible, just terrible,’ said the dog.

‘Why?’

‘No prospects. No variety. Nothing to it. What does it add up to after all? Puppy. Dog. Dead dog – and there you are.’

‘I do feel we could do something better with our lives than just being a tiger and a dog. I men, a dog and a tiger,’ he corrected himself politely.

‘You took the worlds right out of my mouth,’ said the dog.

‘Now how would you suggest we go about it?’ asked the tiger.

This had never happened to the dog before. People were usually busy talking about themselves that they never stopped to enquire about his opinions. It worried him a good deal. He did not want to offend the tiger. He had heard that they were quick tempered animals. Then he had an inspiration.

‘We might walk on our hind legs,’ he said.

‘Is that very inspiring?’ asked the tiger doubtfully.

The dog did not like the tone of the tiger’s voice, so he just plunged on: ‘And use our front paws as hands.’

‘Oh yes, quite,’ said the tiger. He had no idea what hands were but he felt that the dog would think he was not intellectual enough if he admitted it, and might stop talking to him.

‘Then we could live in houses,’ and the dog explained what a house was. ‘We could wear clothes,’ and the dog explained that too. He went on talking and talking, describing all he knew about the village up the road and the people in it, until the tiger thought he was the greatest genius he had ever met.

‘But all this is wonderful,’ said the tiger. I don’t know how you can manage to think such things. I’m so very grateful to you.’

‘Don’t mention it,’ said the dog, ‘anything to oblige.’

‘You don’t know what you’ve done for me,’ said the tiger, getting rather sentimental. ‘Before I met you I was so depressed I could have laid down and died. I thought that there was nothing beyond being a tiger. Nothing higher and nobler. But now you’ve given me something to live for. Do you think,' he said anxiously, ‘that an ordinary tiger like myself could ever hope – I mean if he tried very hard – to be a wonderful person like the ones you described so well?’

The dog looked at him critically. ‘I shouldn’t wonder,’ he said.

‘Oh, I’m so glad. I shall go away into the forest by myself for a bit and practise. Hind legs, I think you said. Yes, I have very strong hind legs,’ he said, thinking of his tiger muscles for the first time with a certain amount of satisfaction. ‘Then there are clothes,’ he said. ‘Clothes.’ Suddenly his spirits went down again and he said, ‘Oh dear, oh dear, it’s all so difficult. I’ll never be able to do it.’

The dog felt a splash on the top of his head and he was just about to say ‘Hullo, raining’ as he always said whenever there was a shower. Then he looked up and saw that big tears were running down the tiger’s cheeks and dripping off the end of his whiskers. The dog felt really sorry for the tiger, and for the first time in his life he broke his rule.

‘Oh, things aren’t as bad as all that,’ he said. ‘Some people manage it.’

‘Who?’ said the tiger, sniffing.

‘People,’ the dog replied, ‘in the forest. You’ll meet them one day maybe.’

'Shall I?' said the tiger excitedly, wriggling his whiskers to get rid of all the tears. ‘How wonderful. But I wouldn’t like to meet them until I can do all the things that they can do. Or least some of them. I’d be so ashamed to be an ordinary good-for-nothing tiger.’

‘That’s the spirit,’ said the dog. ‘Never say die.’

‘I shall start practising straight away.’

‘Easy does it,’ said the dog. ‘Well, I must be off. It’s been nice knowing you.’

It’s been nice knowing you.’

‘Much obliged, I’m sure,’ said the dog, and he trotted off down the road, worrying about his business, which still did not look at all hopeful.

*

T

|

HE TIGER WENT BACK to the other

three tigers and poured out the whole story of how wonderful a tiger could be

if he only aspired to Higher Things and worked hard to be like these people

that the dog had told him about, and who stood on their hind legs and lived in

houses and wore clothes. Of course they would have to give up vulgarities like

killing animals, because these people were all Good and Kind and Loving and

never hurt anybody. The dog hadn’t said that, but he knew it must be so. It

came to him as he was talking to his friends.

This time all the three tigers yawned, not because they wanted to show off their teeth, but because they thought he was talking the most appalling nonsense. But the tiger was too full of his new ambition to notice, and went off into the jungle to practise.

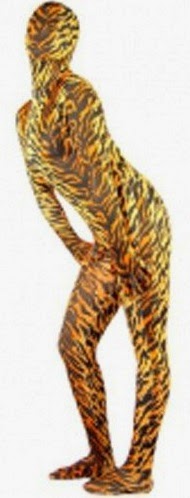

He practised twelve hours a day. He stood on his hind legs until they ached, and he tore down big leaves and put them all over himself and tried to make them look like the things the dog had called clothes. He worked so hard that he almost forgot to eat. His coat grew shabbier and shabbier, his ribs began to show and his whiskers fell out. The other three tigers tried to argue with him, but he just stared over their heads and made silly answers. So they gave up arguing and took turns to watch him, not that he would notice, but from the bushes.

They were really quite good-intentioned tigers, and all though they thought he talked a great deal of nonsense, they did not want him to come to any harm. They also left freshly killed buffaloes on his path. As he was staggering along on his hind legs with his head in the air, he would trip over the dead buffaloes. Then he would say, ‘My, but I am hungry,’ and one or the other of the three tigers could watch to see that he got a good meal.

This time all the three tigers yawned, not because they wanted to show off their teeth, but because they thought he was talking the most appalling nonsense. But the tiger was too full of his new ambition to notice, and went off into the jungle to practise.

He practised twelve hours a day. He stood on his hind legs until they ached, and he tore down big leaves and put them all over himself and tried to make them look like the things the dog had called clothes. He worked so hard that he almost forgot to eat. His coat grew shabbier and shabbier, his ribs began to show and his whiskers fell out. The other three tigers tried to argue with him, but he just stared over their heads and made silly answers. So they gave up arguing and took turns to watch him, not that he would notice, but from the bushes.

They were really quite good-intentioned tigers, and all though they thought he talked a great deal of nonsense, they did not want him to come to any harm. They also left freshly killed buffaloes on his path. As he was staggering along on his hind legs with his head in the air, he would trip over the dead buffaloes. Then he would say, ‘My, but I am hungry,’ and one or the other of the three tigers could watch to see that he got a good meal.

*

ONE DAY the discontented tiger (though he’d quite forgotten that he was ever discontented) was walking along in the forest, sometimes in his hind legs and sometimes on all fours, when he happened to glance between some bushes. Then he felt so weak with happiness that he had to sit down : for there, in the clearing, standing on two legs, and wearing far more clothes than the tiger had ever imagined possible, was one of Them. The tiger blinked his eyes and dug his hind claws into his flank to see if he was dreaming; but he was wide awake, and it was true. He pulled himself together, bit off a big leaf and held it against his chest to look like clothes, and got ready for the moment he had been imagining for so long.

He got up on his hind legs, and he was very proud to see that he could do it very easily. He tottered forward through the bushes and came out into the clearing.

‘Well, hullo,’ he said, but it wasn’t quite distinct, what with his excitement and the leaf in his mouth.

‘There he is,’ said the man. ‘Look out!’

The tiger said the speech he’d planned to say as he came forward. He had to drop the leaf to say it, but he thought the speech was worth it.

‘I’ve waited so long to see you,’ he said. ‘I’ve heard about how wonderful and kind and loving you are, and now at last . . . “ But he could not finish the speech because at that point the man shot him dead.

‘What an ugly beast it is,’ said the man as he lowered his gun.

But one of the three tigers who were looking after the discontented tiger had seen the whole thing happen from some near-by bushes.

‘Well!’ said this tiger, ‘of all the conceited, rude, ill-mannered, snobbish animals I have ever seen, that thing on two legs standing over my poor well-meaning friend is quite the worst. Let me see,’ said the tiger, biting his whiskers, ‘just how far he is away? Ah-ah. Thirty feet, I should say. Yes, thirty feet,’ and out he sprang.

Well, it was exactly thirty feet, and he knocked the man down and dragged him off into the jungle. And whatever happened to him there, he richly deserved it.

*****************************

Moral: Accept what you are.

*

*

ONE DAY the discontented tiger (though he’d quite forgotten that he was ever discontented) was walking along in the forest, sometimes in his hind legs and sometimes on all fours, when he happened to glance between some bushes. Then he felt so weak with happiness that he had to sit down : for there, in the clearing, standing on two legs, and wearing far more clothes than the tiger had ever imagined possible, was one of Them. The tiger blinked his eyes and dug his hind claws into his flank to see if he was dreaming; but he was wide awake, and it was true. He pulled himself together, bit off a big leaf and held it against his chest to look like clothes, and got ready for the moment he had been imagining for so long.

He got up on his hind legs, and he was very proud to see that he could do it very easily. He tottered forward through the bushes and came out into the clearing.

‘Well, hullo,’ he said, but it wasn’t quite distinct, what with his excitement and the leaf in his mouth.

‘There he is,’ said the man. ‘Look out!’

The tiger said the speech he’d planned to say as he came forward. He had to drop the leaf to say it, but he thought the speech was worth it.

‘I’ve waited so long to see you,’ he said. ‘I’ve heard about how wonderful and kind and loving you are, and now at last . . . “ But he could not finish the speech because at that point the man shot him dead.

‘What an ugly beast it is,’ said the man as he lowered his gun.

But one of the three tigers who were looking after the discontented tiger had seen the whole thing happen from some near-by bushes.

‘Well!’ said this tiger, ‘of all the conceited, rude, ill-mannered, snobbish animals I have ever seen, that thing on two legs standing over my poor well-meaning friend is quite the worst. Let me see,’ said the tiger, biting his whiskers, ‘just how far he is away? Ah-ah. Thirty feet, I should say. Yes, thirty feet,’ and out he sprang.

Well, it was exactly thirty feet, and he knocked the man down and dragged him off into the jungle. And whatever happened to him there, he richly deserved it.

*****************************

Moral: Accept what you are.

*

*

NOTE:

The above short story is excerpted

from Aubrey Menen's first novel, the Prevalence of Witches. First published in 1947 and currently out of print, it is a satire on

the incompatibility of values and morals between radically different societies. The Discontented Tiger appears towards the end of the novel. My efforts are limited to typing this

story accurately,

preserving Menen's punctuation and his 1940's colonial

English. Graham Hall, the copyright holder, passed

away in 2005. No idea who is holding copyright now.

I took the effort to type and blog this story because of my frustration that such immortal works are being ignored. If the current copyright holder asks me to take this down, I shall. But I would also request him to say why he has been sleeping over these literary treasures all these years and depriving them to the world.

– Sajjeev Antony

I took the effort to type and blog this story because of my frustration that such immortal works are being ignored. If the current copyright holder asks me to take this down, I shall. But I would also request him to say why he has been sleeping over these literary treasures all these years and depriving them to the world.

– Sajjeev Antony

No comments:

Post a Comment